Thousands of flat-bottomed boats plowed through rough seas under cold gray skies. The smell of diesel fumes and vomit was overwhelming as the small vessels lurched toward the beaches. Waves slapped hard against the plywood hulls while bullets pinged off the flat steel bows.

Frightened men in uniform hunkered down beneath the gunwales to avoid the continuous enemy fire. Suddenly, they heard the sound of the keels grinding against sand and stone. Heavy iron ramps dropped into the surf and the men surged forward into the cold water toward an uncertain fate.

It was 6:28 a.m. on June 6, 1944, and the first LCVPs – Landing Craft, Vehicle and Personnel – had just come ashore on Utah Beach at Normandy. D-Day and the Allied invasion of Europe had commenced.

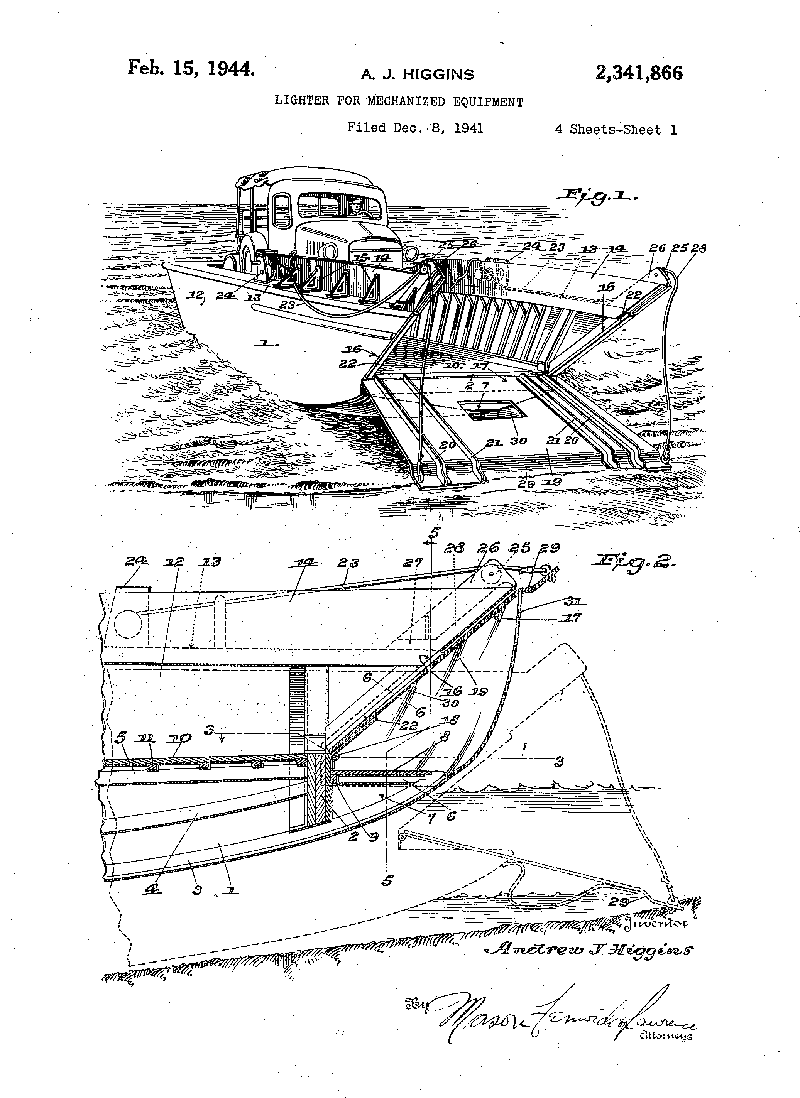

Less than four months earlier, the patent was issued for those very boats. Andrew Jackson Higgins had filed his idea with the U.S. Patent Office on December 8, 1941 – the day after the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor. Now these 36-foot LCVPs – also known as Higgins boats – were being manufactured in the thousands to help American soldiers, marines and seamen attack the enemy through amphibious assaults.

Higgins’ creation had a dramatic impact on the outcome of the Normandy landings 75 years ago, as well as many other naval operations in World War II. The vessel’s unique design coupled with the inventor’s dogged determination to succeed may very well have swung the balance of victory to within grasp of the Allies. At least, that’s what President Dwight D. Eisenhower believed. “Andrew Higgins is the man who won the war for us,” he told author Stephen Ambrose in a 1964 interview.

“His genius was problem-solving,” says Joshua Schick, a curator at the National World War II Museum in New Orleans, which opened a new D-Day exhibit last month featuring a full-scale recreation of a Higgins boat. “Higgins applied it to everything in his life: politics, dealing with unions, acquiring workers, producing fantastical things or huge amounts of things. That was his essence.”

Higgins, a Nebraska native who established himself as a successful lumber businessman in New Orleans, began building boats in the 1930s. He concentrated on flat-bottomed vessels to meet the needs of his customers, who plied the shallow waters in and around the Mississippi River delta. He constantly tinkered with the concept as he sought to improve his boats to better match the ideal in his own mind of what these boats should be.

During the Prohibition era, Higgins had a contract with the U.S. Coast Guard to build fast boats for chasing after rum runners. There are rumors that he then went to the rum runners and offered to sell them even faster boats. Schick doesn’t come right out and confirm the stories, but he doesn’t deny them either.

“That stuff is always fun to smile and chuckle about, but no one ever keeps a record saying that’s what they did,” he diplomatically states.

Higgins’ innovative spirit enabled a series of breakthroughs that led to the eventual design that became his namesake boat. First was the spoonbill bow that curled up near the ramp, forcing water underneath and enabling the craft to push up on to the shore and then back away after offloading. A ridge was later added to the keel, which improved stability. Then, a V-shaped keel was created and that allowed the boat to ride higher in the water.

“There was no task Higgins couldn’t do,” Schick says. “He would find a way to do something, then find a way to do it better.”

Higgins started making landing craft for the Navy when World War II began. He built a 30-footer, the Landing Craft Personnel (LCP), based on government specifications but he insisted a larger boat would perform better. The Navy relented and he came up with a 36-foot version, the Landing Craft Personnel Large (LCPL), that would become the standard for the rest of the war.

The Marines weren’t completely satisfied with this boat, though. The design required personnel and equipment to be offloaded by going over the side. In 1942, the Marines requested a ramp be added to the front of the vessel for faster egress.

“Higgins takes the LCPL, cuts the bow off, puts a ramp on it and then it becomes the LCVP, which becomes the famous Higgins Boat,” Schick says.

That landing craft, often referred to as “the boat that won World War II,” could quickly carry up to 36 men from transport ships to the beaches. It also could haul a Willys Jeep, small truck or other equipment with fewer troops. Higgins’ earlier modifications along with an ingenious protected propeller system built into the hull enabled the boats to maneuver in only 10 inches of water.

This version became the basis for a variety of designs and different configurations during World War II. LCA (Landing Craft Assault), LCM (Landing Craft Mechanized), LCU (Landing Craft Utility), LCT (Landing Craft Tank) and other models followed the same fundamental style, all built by Higgins or under license with his company, Higgins Industries. Higgins was named on 18 patents, most of which were for his boats or different design adaptations to the vessels.

At the height of World War II, Higgins Industries was the largest employer in the New Orleans area. More than 20,000 whites, blacks, women, elderly and handicapped people worked at seven plants in one of the first modern integrated workplaces in America. They produced a variety of landing craft in different shapes and sizes, PT boats, supply vessels and other specialized boats for the war effort. Higgins developed a reputation for being able to do the impossible. Once, the Navy asked him if he could come up with plans for a new boat design in three days. “Hell,” he replied. “I can build the boat in three days.” And that is exactly what he did.

“The man was all about efficiency and getting things done,” Schick says. “The Navy began to realize that if there was an impossible task, just give it to Higgins and he’ll do it

The secret to Higgins success may have been his personality. He was driven to succeed and never let barriers slow him down. He often bulled his way through or over bureaucratic quagmires, labor difficulties, material shortages and negative-thinking people with a brusk attitude and a few salty words.

“As long as Higgins was the one in charge and didn’t have to rely on other people, he could bust through any obstacle that came in his way,” Schick says. “That attitude of determination and hard work helped him solve just about any issue.”

The Higgins Boat saw action in many amphibious landings throughout World War II. In addition to Normandy, they were used in Sicily, Anzio, Tarawa, Iwo Jima, Saipan, Okinawa, Peleliu and countless other beaches in the European and Pacific theaters of operation.

More than 20,000 of the Higgins-designed landing craft were made from 1942 to 1945, but fewer than 20 remain today. To commemorate D-Day, one of the surviving Higgins boats is on display, through July 27, in the gardens outside of the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office headquarters and National Inventors Hall of Fame Museum in Alexandria, Virginia.

Their legacy cannot be understated. They changed the course of the war and provided the Allies with an ability to strike anywhere with speed and effectiveness – all because of the incredible pluck of the inventor, who was inducted into the National Inventors Hall of Fame this year.

“Higgins was a man ahead of his time,” Schick says. “He had attitude and determination. He knew how to lead and organize. He surrounded himself with smart people and knew how to get the most out of them. He was a strong-minded man.”

Source: smithsonianmag.com